Etching: The Creative Process

In the catalogue essay for an exhibition of prints held in 1891 at Paris’s popular Galeries Durand-Ruel, the critic Roger Marx effusively wrote of etching’s status at that time: “Was it ever more desirable, more deserving of museums’ attentions, of collectors’ searches? The late nineteenth century … will remain for original etching a turning point, a period of absolute efflorescence.”1 As Marx’s words suggest, etching underwent a revolutionary transformation during the second half of the nineteenth century. Historically, the medium was practiced by artists including Rembrandt van Rijn and Jacques Callot, but interest had waned by the early 1800s, as other printmaking techniques such as engraving and lithography grew in popularity. Around mid-century, the publisher Alfred Cadart and printer Auguste Delâtre initiated what became a full-scale revival of etching, arousing an interest among printmakers that has lasted to this day.

Above all, the nineteenth-century etching revival was centered on technique. New manuals and treatises on the process allowed artists to teach themselves how to etch, and the ready availability of tools and personal presses facilitated work in the privacy of a studio rather than in a print shop. More than ever before, artists could produce and print their own work without the intermediation of a trained master printer or expensive equipment. This new availability of technical information, more broadly, encouraged artists to work creatively with etching; with all the necessary materials at their disposal, they could freely and actively experiment. The private conditions in which their prints were produced, viewed, and collected encouraged artists to pursue new formal effects as well as subject matter that might have been difficult to realize in more public media, such as painting. This publication focuses on the creativity and experimentation that proliferated in these years, during and after etching’s revival, and the centrality of process in this important shift.

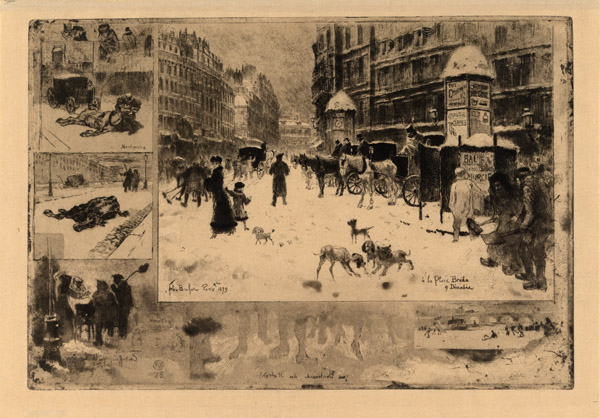

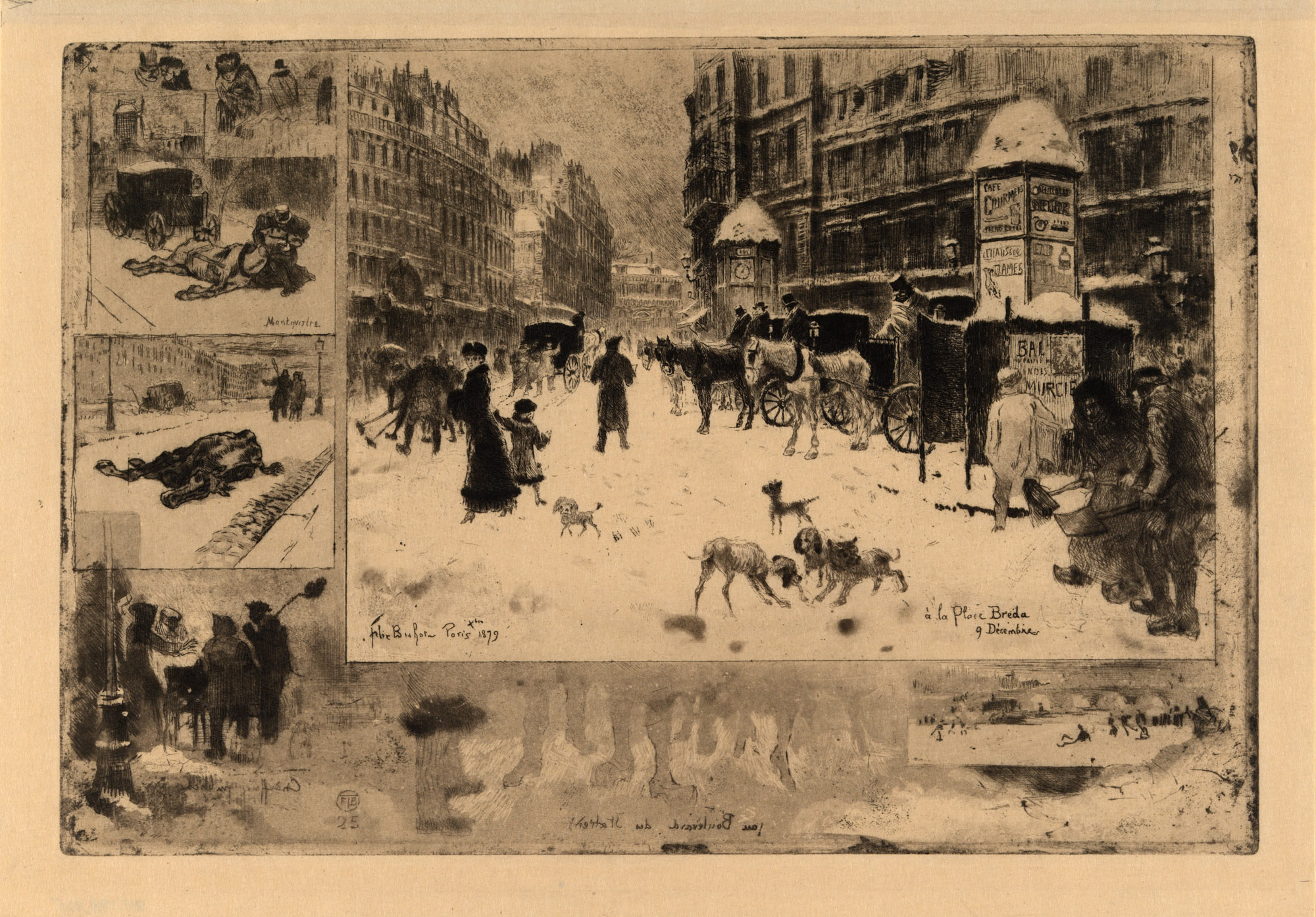

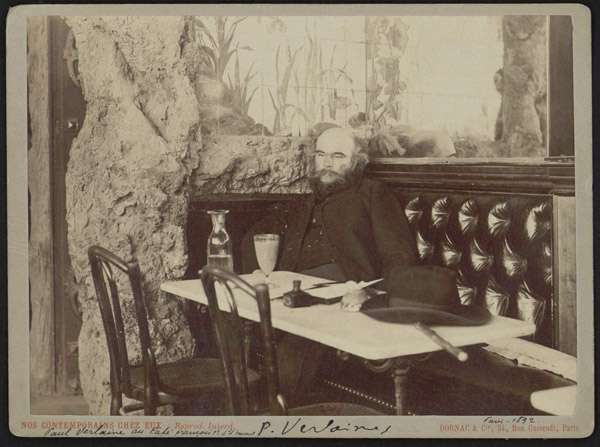

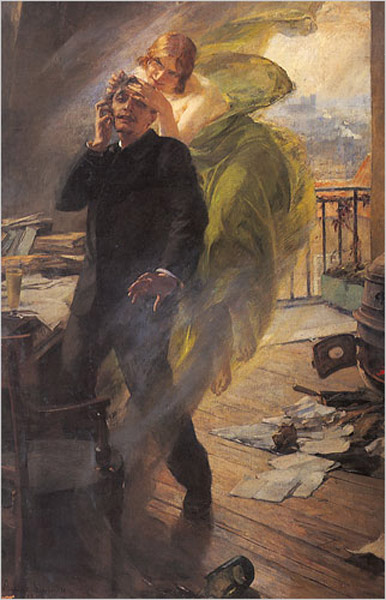

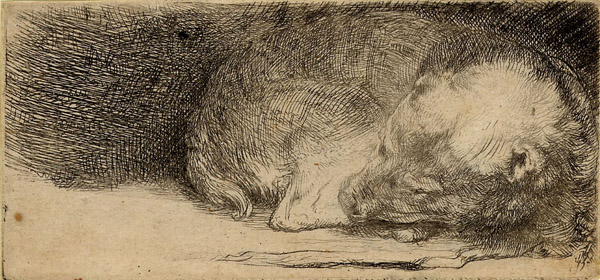

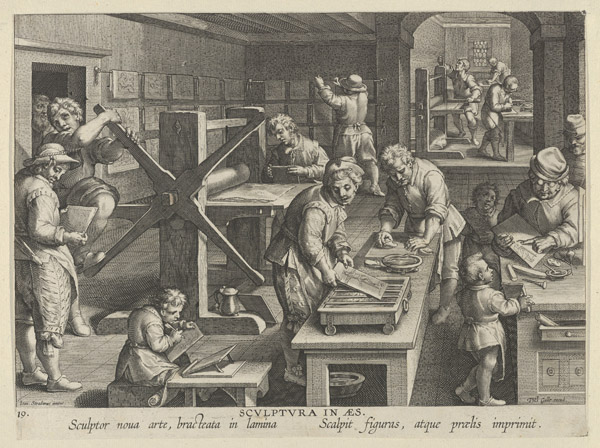

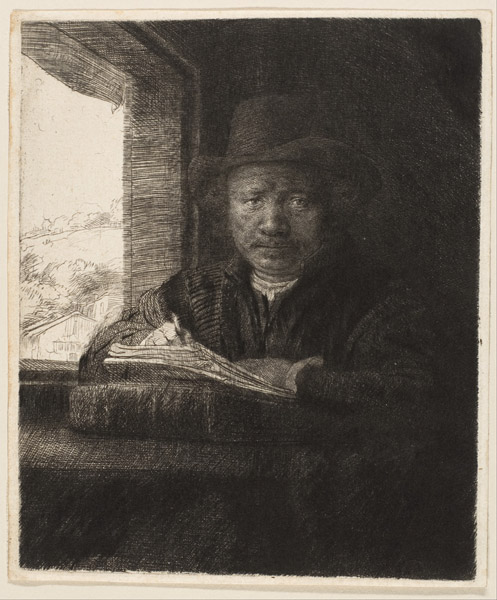

The practice of etching began to fundamentally change around 1862, when

a group of artists formed an organization called the Société des

Aquafortistes. Supported by Cadart and Delâtre, the group aimed to

transform the public perception and artistic practice not only of

etching, but of the graphic arts in general. At the time of the group’s

formation, printmaking was used mostly as a means of producing

affordable copies of paintings for middle-class audiences. These prints

were often made either using engraving, whose practitioners required

long and specialized training, or lithography, which required materials

and equipment only available in specialized shops. The artists,

publisher, and printer who formed the Société des Aquafortistes hoped to

counter this use of printmaking as a reproductive art form and

reestablish its originality. To do so, they looked to past masters of

the medium, especially Rembrandt, who they saw as the ultimate example

of a “painter-printmaker”—a practitioner focused on making prints as a

means of formal exploration and personal expression, rather than

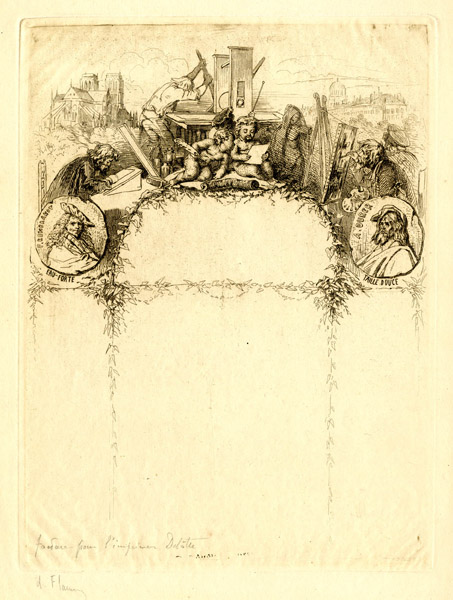

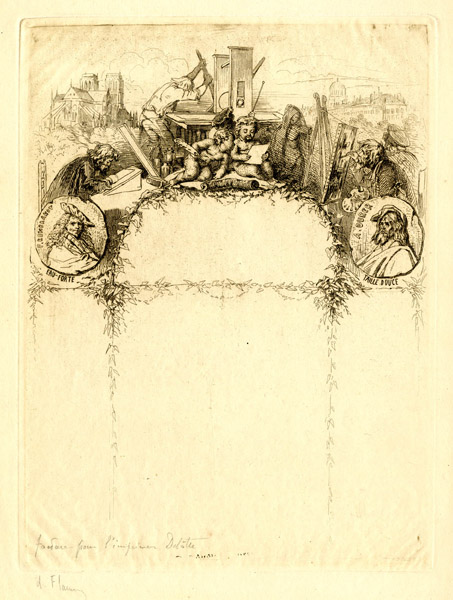

entrepreneurial gain. A design by the artist Léopold Flameng for a

letterhead used for invoices by Delâtre 2 clearly suggests the

printer’s ambitions for the organization in its decorative depiction of

an artist who etches, paints, and prints his own work. The Parisian

cityscape makes up the background, with portrait medallions of Dürer and

Rembrandt decorating the foreground.

2 clearly suggests the

printer’s ambitions for the organization in its decorative depiction of

an artist who etches, paints, and prints his own work. The Parisian

cityscape makes up the background, with portrait medallions of Dürer and

Rembrandt decorating the foreground.

A dramatic revival of etching followed the formation of the Société and

lasted into the 1870s. At the organization’s headquarters, artists,

printers, publishers, dealers, collectors, and critics gathered to share

their enthusiasm, obtain training in the medium, and view or purchase

newly produced works by members. Cadart and Delâtre also regularly

published albums presenting a selection of prints either by an

individual artist or by a group of member artists—such as

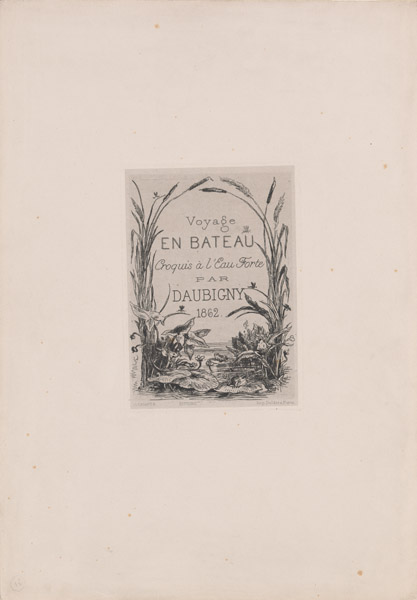

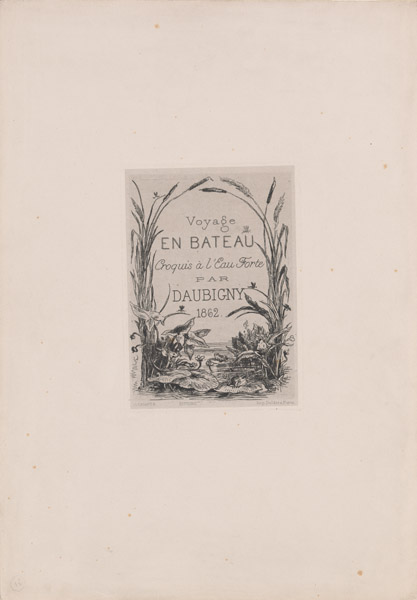

Voyage by Boat, a set of etchings by Charles François Daubigny

depicting the path of two travelers. 3 Their publication of the

portfolio Eaux-fortes modernes similarly offered collectors a

preselected group of prints, accompanied by essays on

the medium by prominent critics and writers. Easily circulated among

collectors and dealers, these projects, as well as the sense of

community created through the organization’s physical space,

successfully reestablished the status of etching during the 1860s.

3 Their publication of the

portfolio Eaux-fortes modernes similarly offered collectors a

preselected group of prints, accompanied by essays on

the medium by prominent critics and writers. Easily circulated among

collectors and dealers, these projects, as well as the sense of

community created through the organization’s physical space,

successfully reestablished the status of etching during the 1860s.

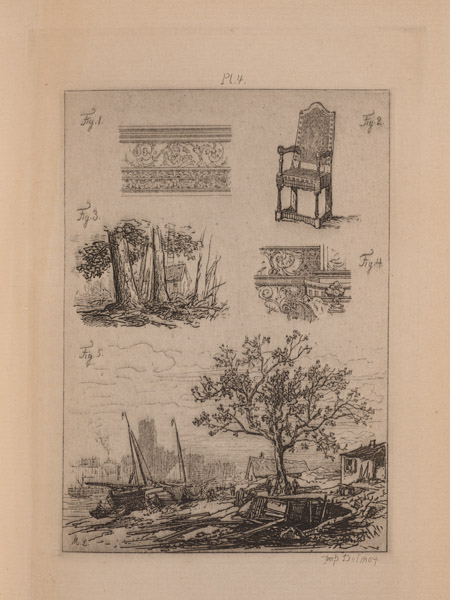

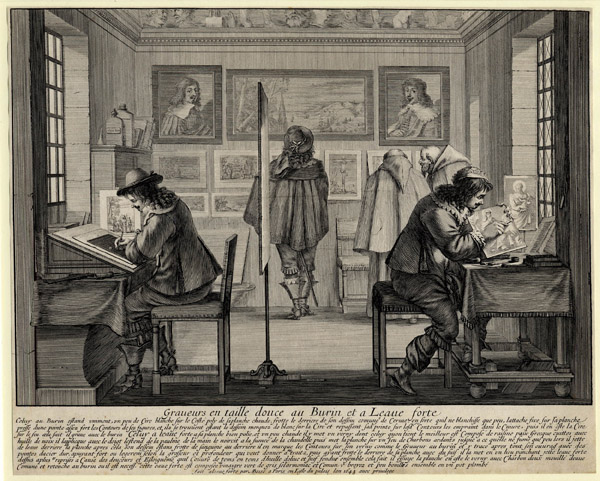

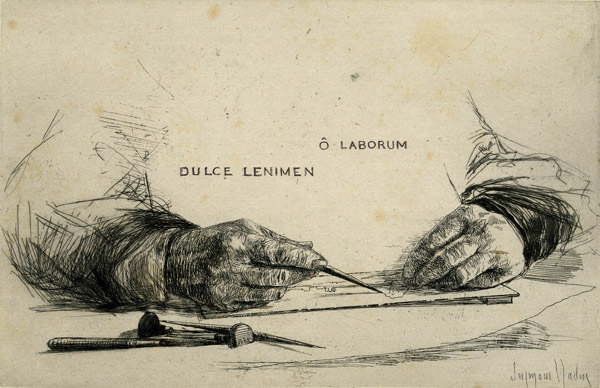

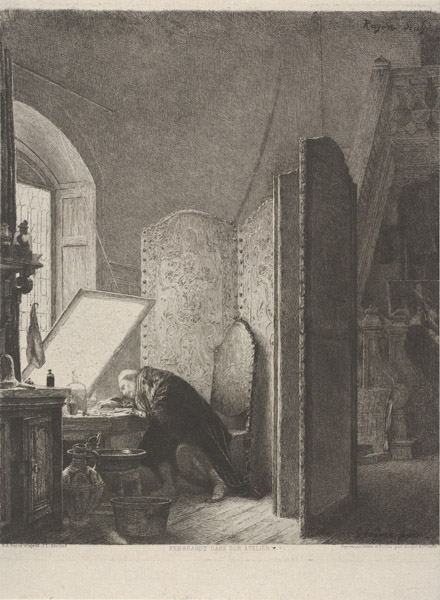

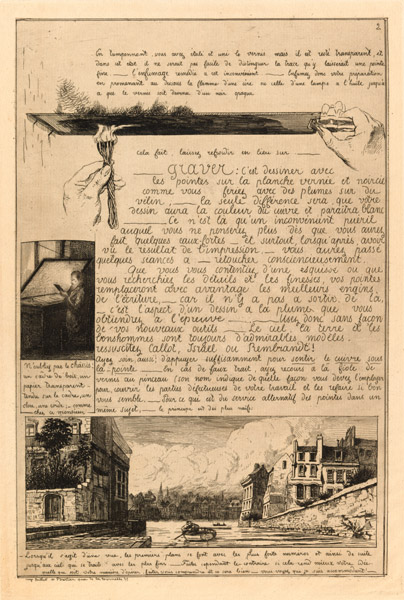

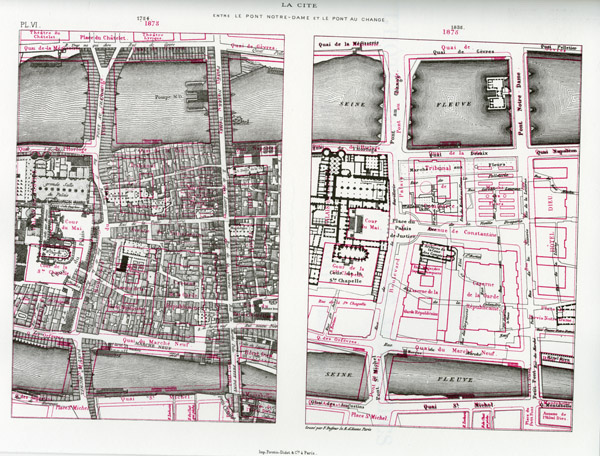

Although the etching revival and the contributions of the Société des

Aquafortistes are often seen as turning points for the medium, less

attention has been devoted to the years that followed and the important

continued impact that the movement had during that time—especially

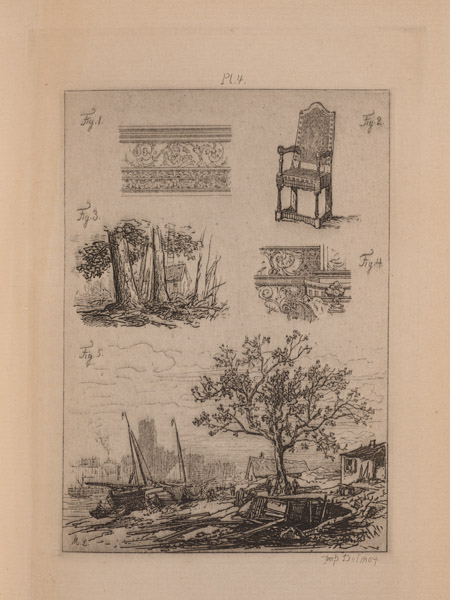

regarding the greater availability of technical information. One of the

revival’s most important contributions included member artist Maxime

Lalanne’s Treatise on Etching, 4 which continued to be

reprinted and revised in the decades following its publication in 1866,

each time offering greater encouragement for artists interested in an

experimental and independent approach to etching. An etcher of highly

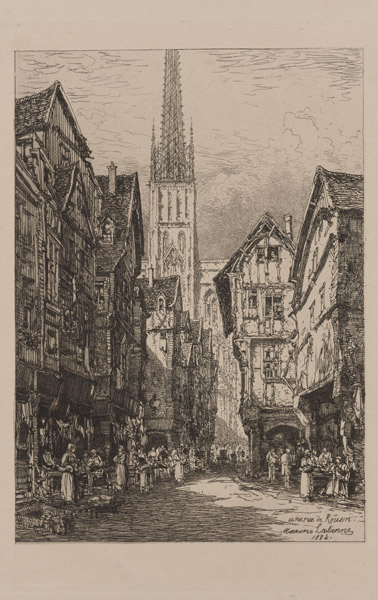

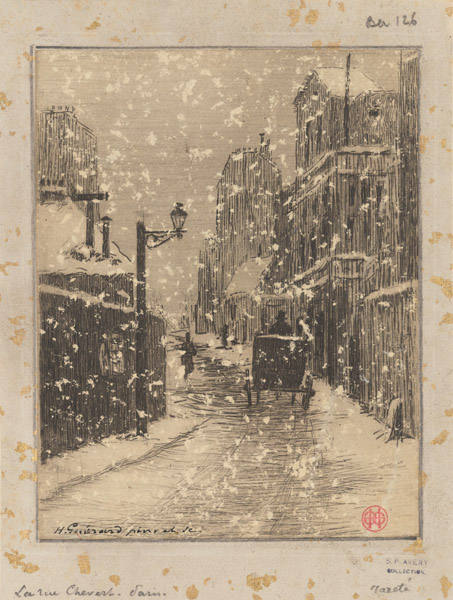

detailed cityscapes,

4 which continued to be

reprinted and revised in the decades following its publication in 1866,

each time offering greater encouragement for artists interested in an

experimental and independent approach to etching. An etcher of highly

detailed cityscapes, 5 Lalanne was known less by his art and more

by his manual. His text took the form of an informal conversation

between the author and a novice student, and its accessible,

nontechnical approach was seen as a vast improvement upon the handbook

previously used most, Abraham Bosse’s On the Manner of Etching with

Acid and with a Burin, and of Dark-Manner Engraving,

5 Lalanne was known less by his art and more

by his manual. His text took the form of an informal conversation

between the author and a novice student, and its accessible,

nontechnical approach was seen as a vast improvement upon the handbook

previously used most, Abraham Bosse’s On the Manner of Etching with

Acid and with a Burin, and of Dark-Manner Engraving, 6 published

two centuries earlier. As the critic Charles Blanc described in a

preface to the first edition of Lalanne’s text, “Abraham Bosse wrote for

those who know, while [Lalanne writes] for those who do not know.”7

6 published

two centuries earlier. As the critic Charles Blanc described in a

preface to the first edition of Lalanne’s text, “Abraham Bosse wrote for

those who know, while [Lalanne writes] for those who do not know.”7

Lalanne’s original text provided an overview of etching from start to finish, introducing topics from a theoretical discussion of the “definition and character” of the medium to preparing the plate, biting, and printing, as well as the various materials that could be used in etching. In addition, the author addressed an extensive list of accidents that could take place during the process, advising the reader on how to work through them. On a methodological level, Lalanne also encouraged a new and specific approach to etching, promoting a free and expressive line and emphasizing the importance of aligning subject and technique.8 The eight later editions of the treatise gradually placed greater emphasis on working independently, including printing one’s own work.9 The translated edition of 1880, for example, offered an addendum section of notes with a precise description of setting up to print at home.10 The treatise offered new possibilities for self-instruction and, as a book, was circulated widely, allowing artists worldwide, both those connected to and disparate from the etching revival in Paris, the knowledge to begin making prints.

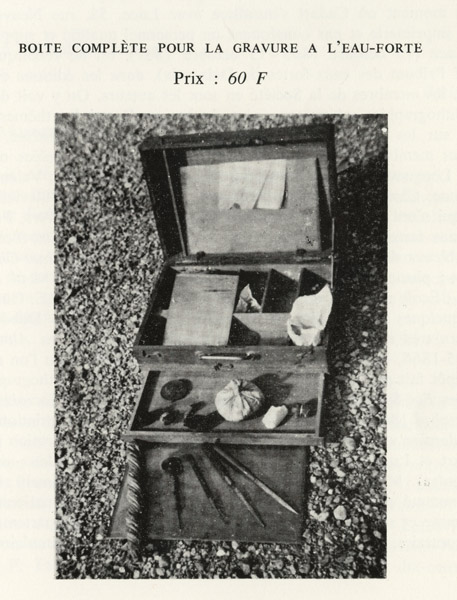

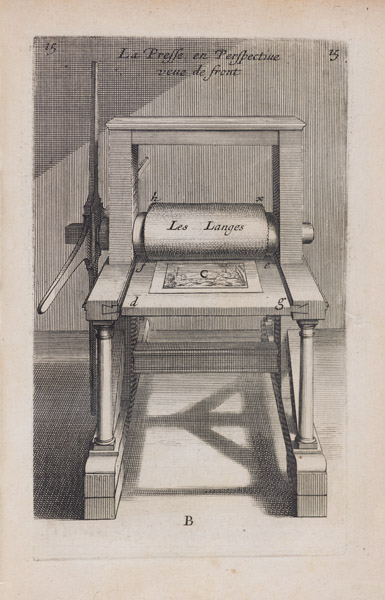

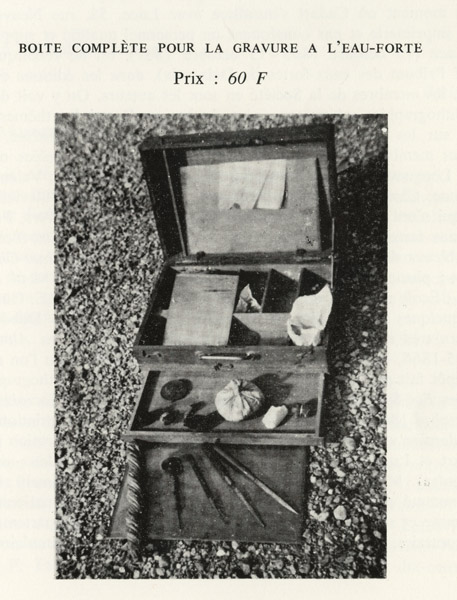

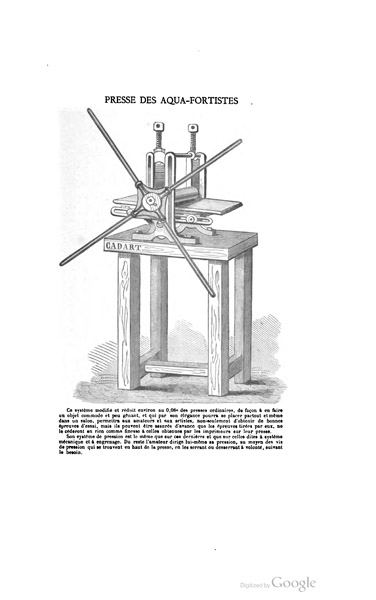

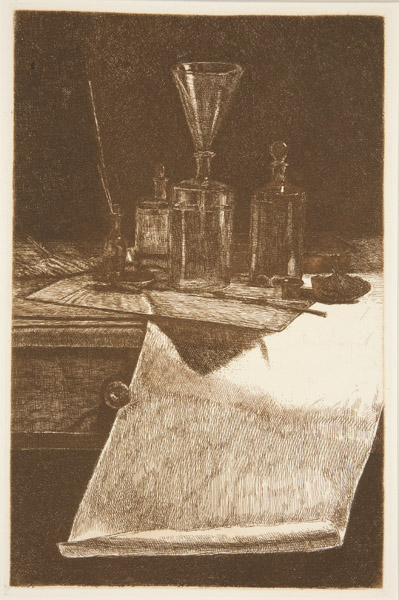

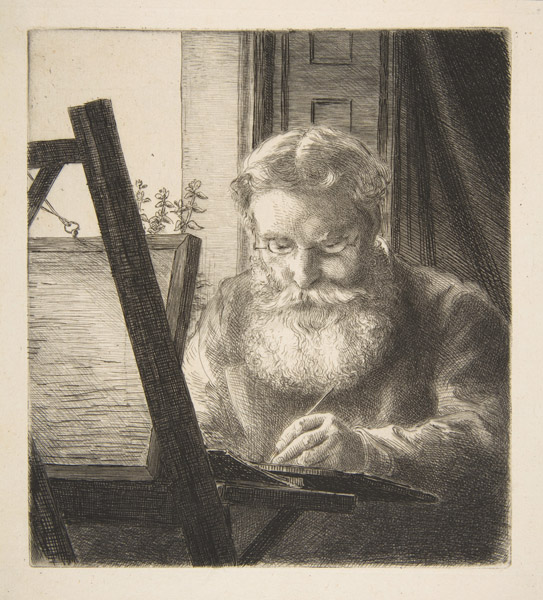

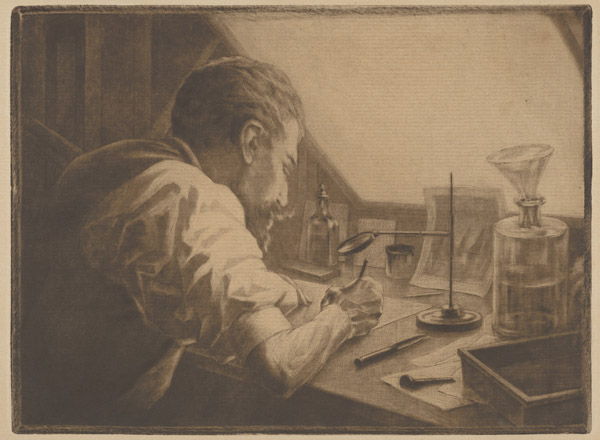

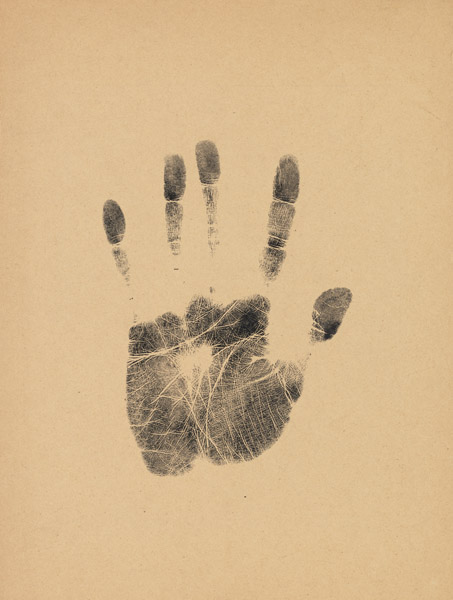

Once they had learned the basics of etching, artists could benefit from

the new availability of personal and easy-to-use tools and materials.

Cadart sold a boîte complète pour la gravure à l’eau-forte (etching

kit) from his Parisian shop. The modest sum of sixty francs could buy

an organized and portable package containing tools such as a burnisher,

needle, and roulette, as well as wax ground and aquatint. 11 A

deluxe version was also available for 100 francs.12 This kit allowed

artists to work on etchings in virtually any location, and to prepare

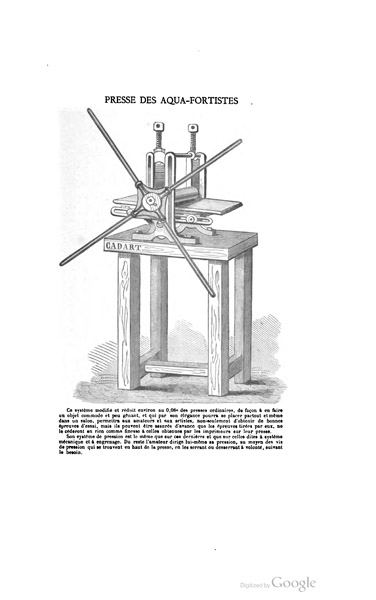

their own plates. Artists were soon also able to undertake their own

printing. In the same year of Lalanne’s manual, the British artist and

critic Philip G. Hamerton published his Etchers and Etching, which

asserted that “every one [sic] who etches ought to have a press in his

own house.”13 Hamerton himself designed a small personal press that

became available in 1870. Around the same time, Cadart began to sell a

similar portable press,

11 A

deluxe version was also available for 100 francs.12 This kit allowed

artists to work on etchings in virtually any location, and to prepare

their own plates. Artists were soon also able to undertake their own

printing. In the same year of Lalanne’s manual, the British artist and

critic Philip G. Hamerton published his Etchers and Etching, which

asserted that “every one [sic] who etches ought to have a press in his

own house.”13 Hamerton himself designed a small personal press that

became available in 1870. Around the same time, Cadart began to sell a

similar portable press, 14 which artists could fit and work with

in their own studios, for the affordable cost of one hundred fifty

francs.15 An announcement published in the journal Union des Arts

described these new resources, saying that “those who have the desire to

try [etching] … will find at Cadart and Luquet everything they

could ever need … they will happily show anyone who stops by …

all the different processes that form the basis of etching.”16

Legislation passed in 1881 abolished a requirement that such equipment

be registered and authorized, further encouraging artists to acquire

their own presses, and artists began to work more independently than

ever before.17 By 1890, the critic Philip Burty would write, “Today,

almost all etchers have taken up printing their works, to vary the

effects of printing, all owning their own presses in their studio.”18

14 which artists could fit and work with

in their own studios, for the affordable cost of one hundred fifty

francs.15 An announcement published in the journal Union des Arts

described these new resources, saying that “those who have the desire to

try [etching] … will find at Cadart and Luquet everything they

could ever need … they will happily show anyone who stops by …

all the different processes that form the basis of etching.”16

Legislation passed in 1881 abolished a requirement that such equipment

be registered and authorized, further encouraging artists to acquire

their own presses, and artists began to work more independently than

ever before.17 By 1890, the critic Philip Burty would write, “Today,

almost all etchers have taken up printing their works, to vary the

effects of printing, all owning their own presses in their studio.”18

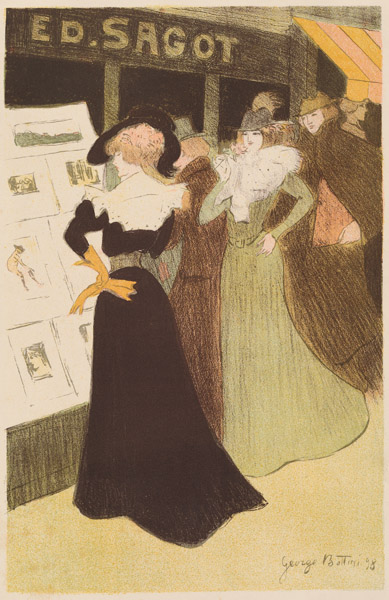

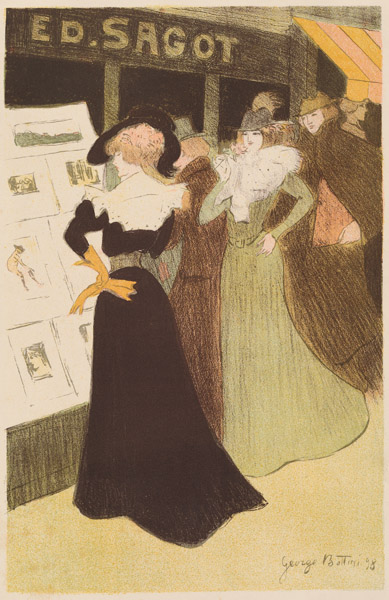

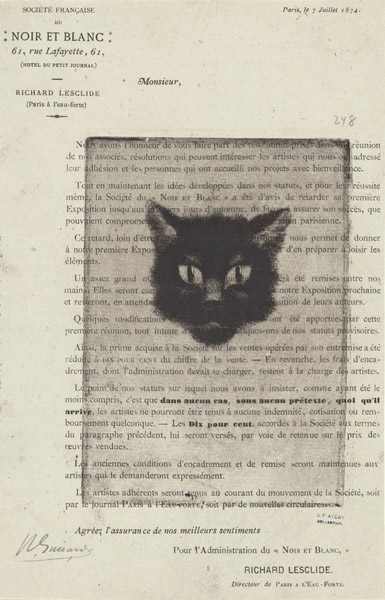

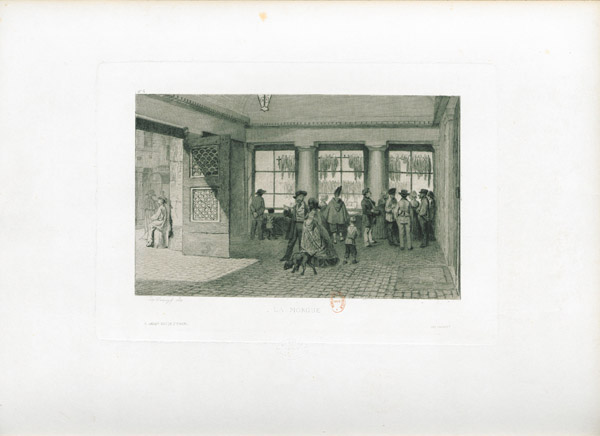

Etchers were also encouraged by the growing interest in their work among

collectors during the late nineteenth century. In comparison to the

market for paintings, modest prices bolstered the demand for etchings,

and a number of dealers soon began to cater to it. Edmond Sagot, for

example, transformed his bookshop into a gallery for prints 19 in

1884 and corresponded extensively with enthusiastic collectors about his

holdings and the relative merits of various artists.20 Like several

other dealers at the time, including Gustave Pellet and Victor Prouté,

Sagot circulated a catalogue listing available works, dramatically

extending the geographic reach of the print market.21 In addition to

visiting these dealers, many collectors purchased works from artists

themselves, calling on them at their studios to discuss their work and

view new prints. Collectors could also build their connoisseurial skills

by studying the vast holdings of prints available in the study room of

the Bibliothèque nationale de France and, nearby, at Paris’s Hôtel

Drouot, an auction house that regularly held sales of prints dispersed

from famous collections.22

19 in

1884 and corresponded extensively with enthusiastic collectors about his

holdings and the relative merits of various artists.20 Like several

other dealers at the time, including Gustave Pellet and Victor Prouté,

Sagot circulated a catalogue listing available works, dramatically

extending the geographic reach of the print market.21 In addition to

visiting these dealers, many collectors purchased works from artists

themselves, calling on them at their studios to discuss their work and

view new prints. Collectors could also build their connoisseurial skills

by studying the vast holdings of prints available in the study room of

the Bibliothèque nationale de France and, nearby, at Paris’s Hôtel

Drouot, an auction house that regularly held sales of prints dispersed

from famous collections.22

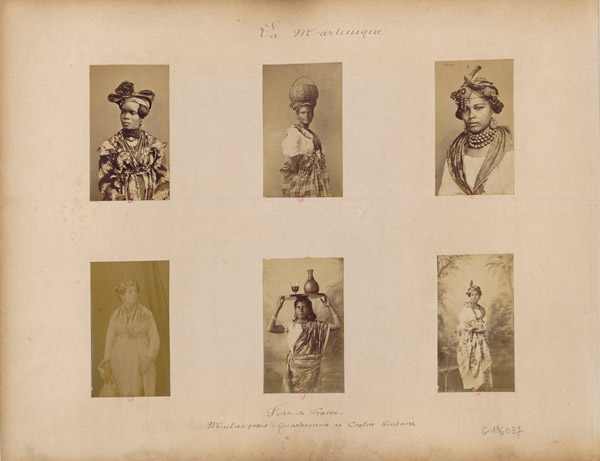

To facilitate these interactions, a wide body of literature began to be published in the late nineteenth century to assist collectors in better understanding the market for etching, as well as key artists and aspects of technique. Beginning in the 1880s, a number of manuals—often written by print connoisseurs themselves—were published with the aim of allowing collectors to educate themselves. Issued from 1885 through 1892, Henri Beraldi’s Les Graveurs du XIXe Siècle was the first to focus exclusively on contemporary prints, providing biographical information on important etchers along with lists of their known prints and technical notes gleaned from his own collecting practices.23 Shortly after, in 1906, the collector, critic, printmaker, and occasional dealer Loys Delteil began publishing his Le Peintre-Graveur illustré, ultimately producing thirty-one volumes devoted to individual printmakers, with illustrations to facilitate collectors’ research. In addition to these books, a number of new journals catered specifically to print collectors. Periodicals such as L’Estampe and L’Estampe et l’affiche provided a centralized source on the Parisian print world, including information about dealers, exhibitions, artists, auctions, and logistics of collecting. They also encouraged interaction from readers, soliciting opinions and experiences for publication in their pages.24 This wide body of literature made etching more accessible to collectors and allowed artists to work with the knowledge of a ready and interested market.

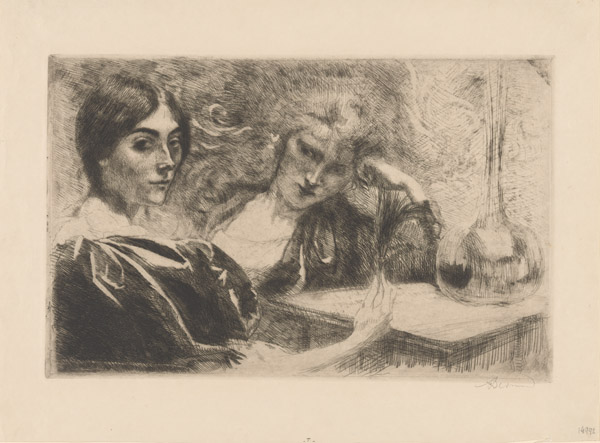

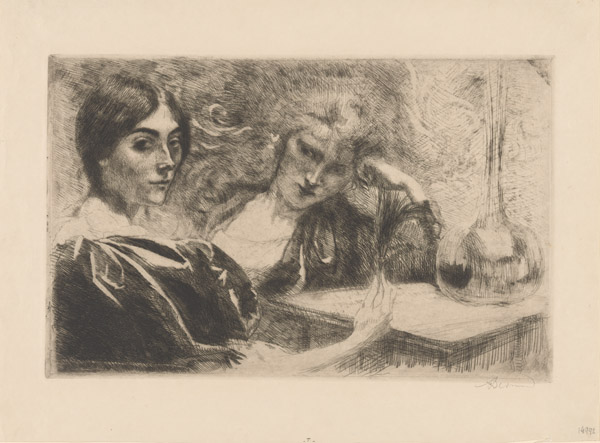

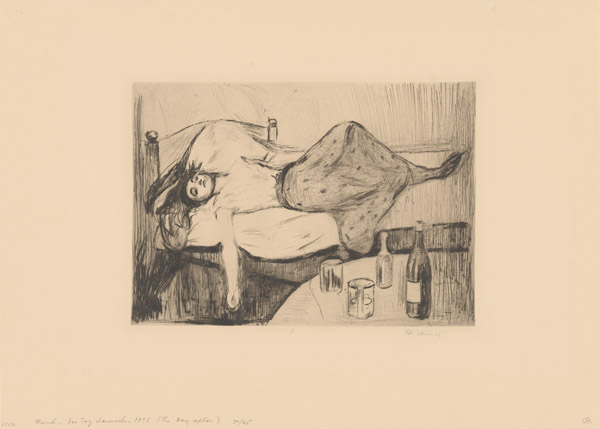

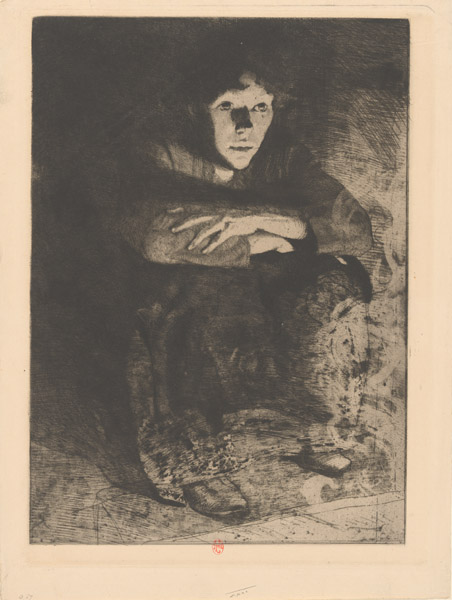

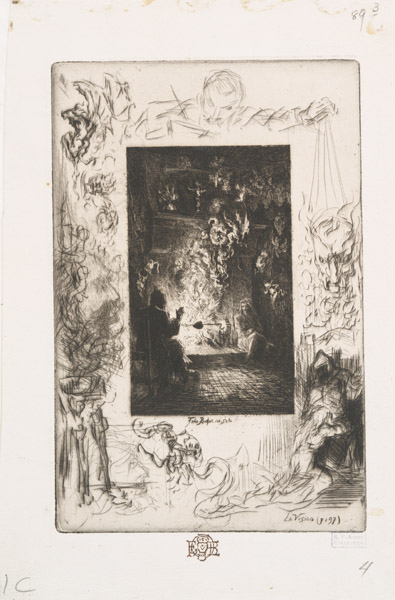

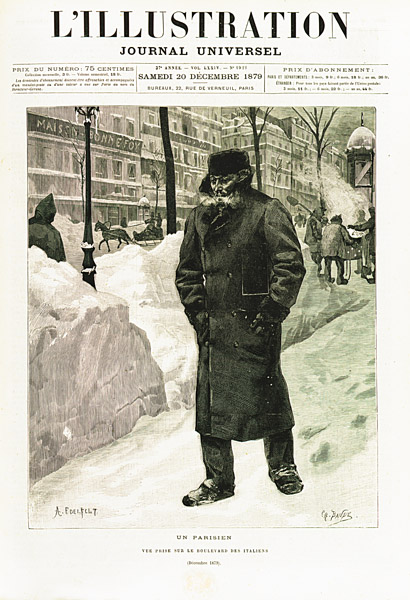

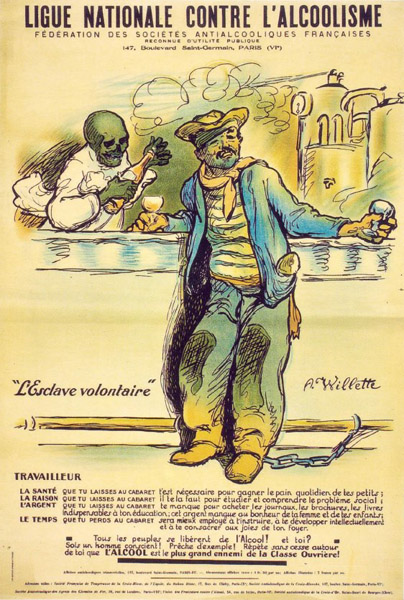

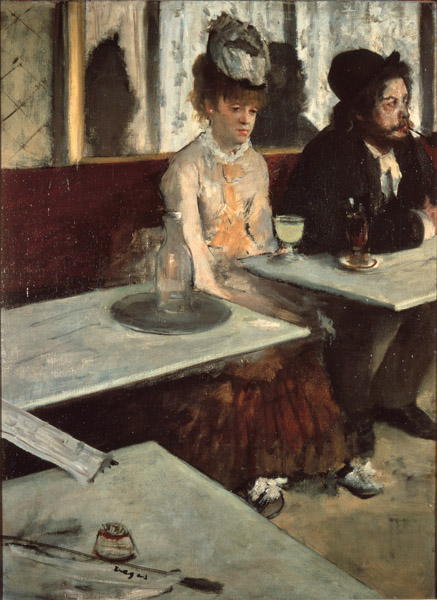

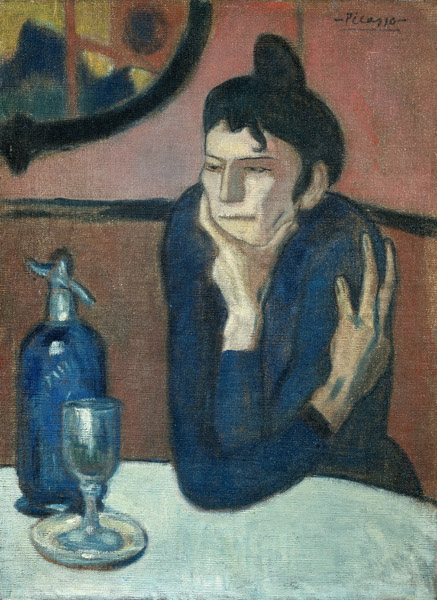

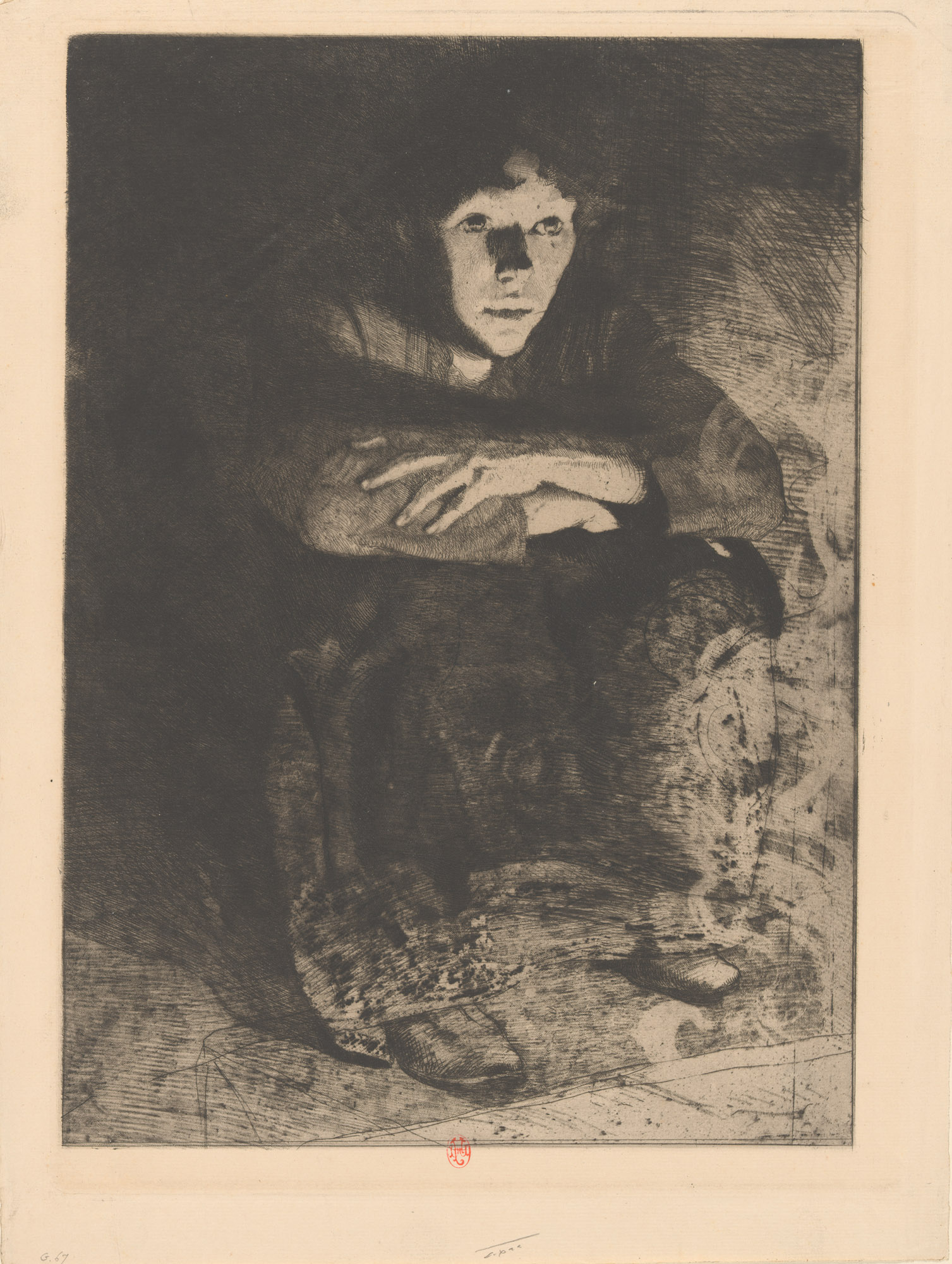

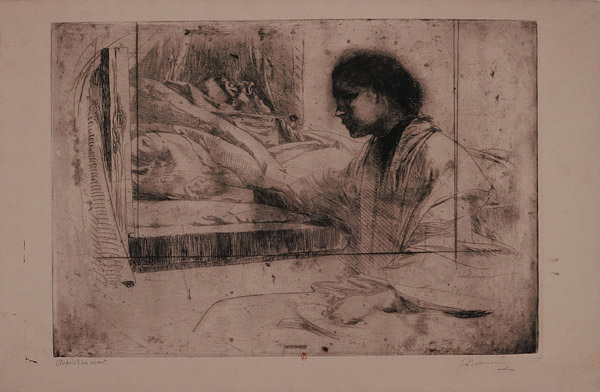

The enthusiasm of collectors encouraged artists to experiment not only

with process, but also with new and often socially relevant subject

matter, such as poverty, urban transformation, and

the social roles of women. Because etchings could be produced in the

privacy of an artist’s studio and marketed directly to interested

collectors, they could address topics that might arouse controversy in

media such as painting, which was often necessarily displayed and viewed

in public places such as galleries or exhibition spaces.25 With

greater knowledge of technique, artists used the formal qualities

inherent to etching to enhance their depiction of psychologically and

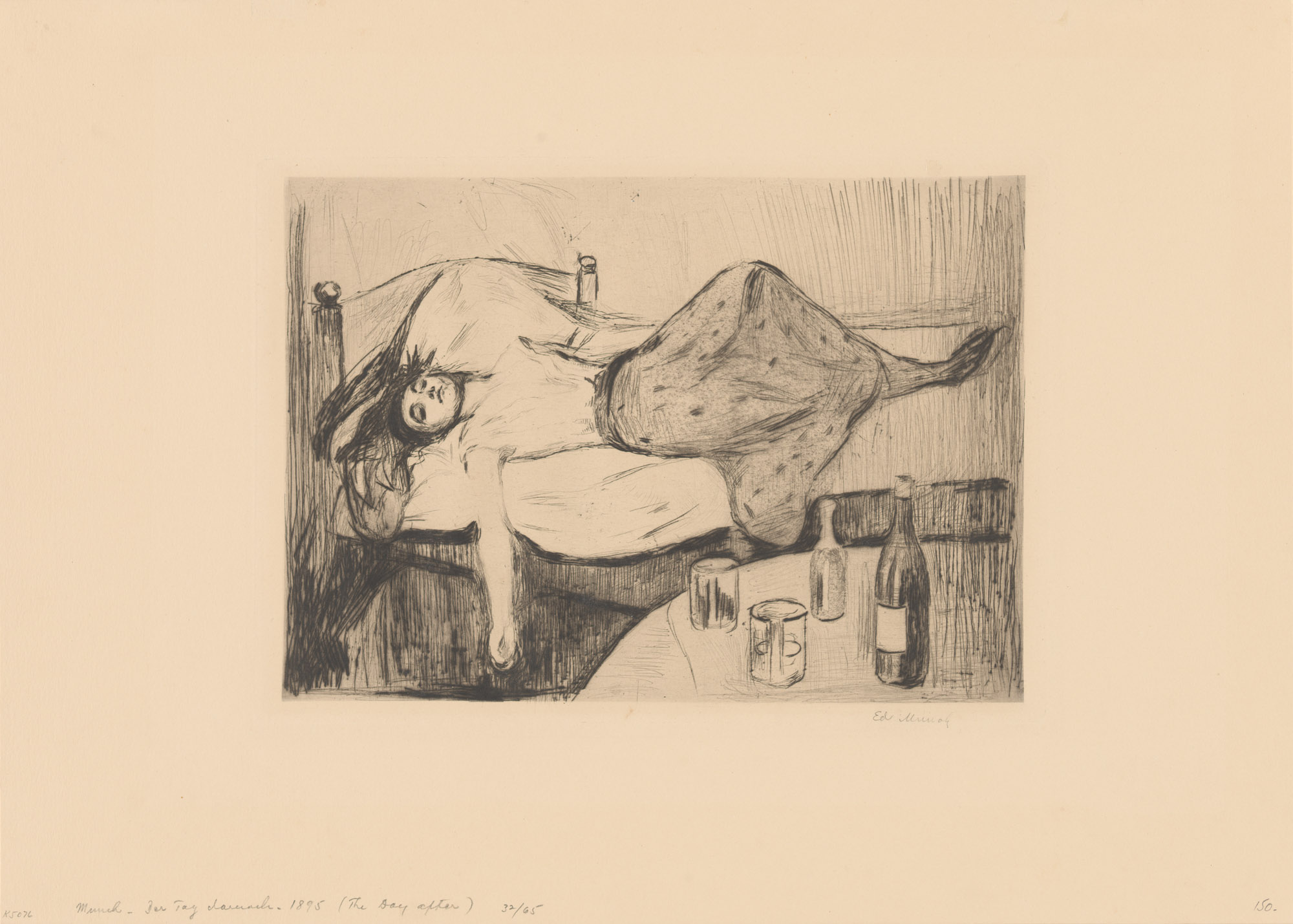

politically charged subjects. For his depiction of two young female drug

users in The Morphine Addicts, 26 for example, Albert Besnard

rendered one woman in dark tones, staring directly at the viewer, and

the other in loose sketchy lines that allow her to fade distinctly into

her surroundings, evoking the mental release of the drugs the pair

consumes. The scene is dominated by the large feather one woman holds,

mirrored by a plume of smoke encircling them. The latter was created by

applying an acid-resistant varnish to Besnard’s copper plate (called

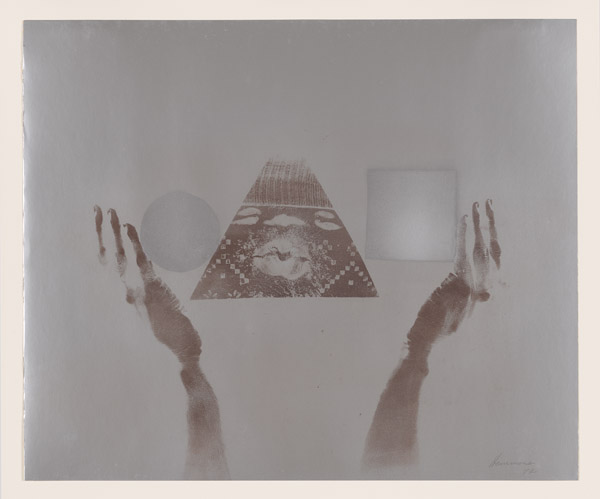

“stopping out”), preventing a line from etching in that area. In his

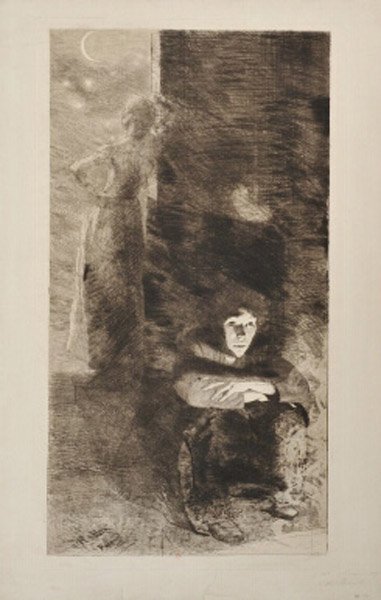

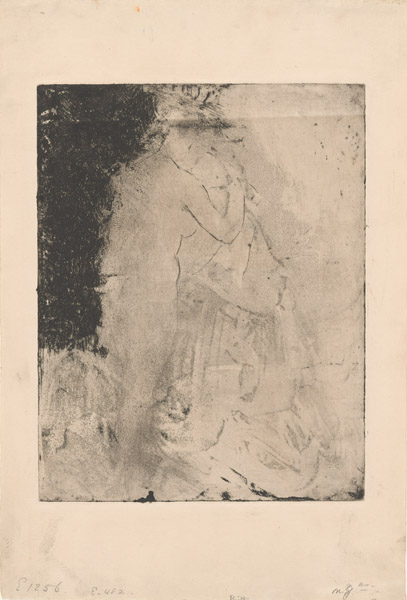

depiction of a clandestine meeting between two lesbians in Farewell at

the Parc d’Auteuil, Félicien Rops likewise used process to emphasize

the meeting’s concealment, experimenting with cleanly printing his plate

26 for example, Albert Besnard

rendered one woman in dark tones, staring directly at the viewer, and

the other in loose sketchy lines that allow her to fade distinctly into

her surroundings, evoking the mental release of the drugs the pair

consumes. The scene is dominated by the large feather one woman holds,

mirrored by a plume of smoke encircling them. The latter was created by

applying an acid-resistant varnish to Besnard’s copper plate (called

“stopping out”), preventing a line from etching in that area. In his

depiction of a clandestine meeting between two lesbians in Farewell at

the Parc d’Auteuil, Félicien Rops likewise used process to emphasize

the meeting’s concealment, experimenting with cleanly printing his plate 27 and then reprinting with a thickly wiped layer of ink that

envelops the pair in a deep, murky shadow,

27 and then reprinting with a thickly wiped layer of ink that

envelops the pair in a deep, murky shadow, 28 changing the scene’s tone literally and figuratively.

28 changing the scene’s tone literally and figuratively.

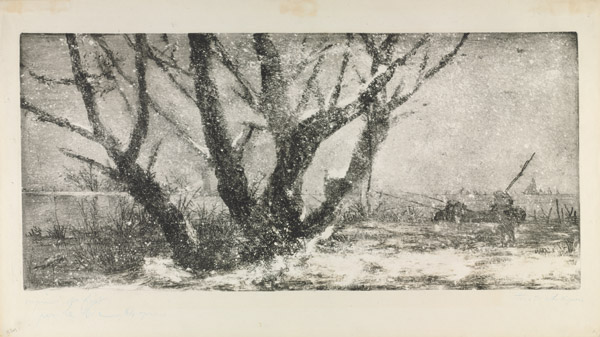

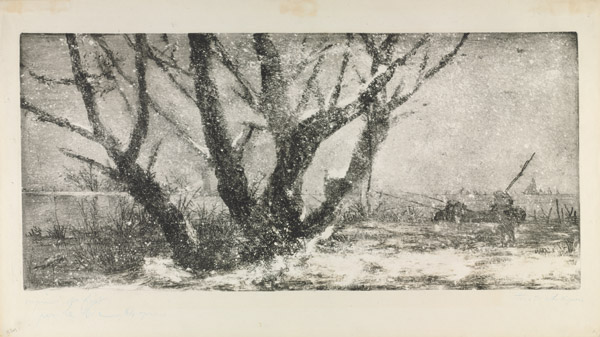

Etchers in late nineteenth-century Paris widely took up this

experimental approach, seeing traditional technique as a starting point

rather than an end in itself. Ludovic Lepic, for instance, developed a

process—which he termed l’eau-forte mobile (variable etching)—that

drew as much on painting as printmaking. By wiping ink selectively on

the surface of a copper plate—an approach which had already existed and

is today known as monotype—Lepic was able to create multiple unique

variations on his prints. His series Views from the Banks of the

Scheldt was produced from the same printing plate, which showed

windmills and ships in the distant background and, in the foreground, a

grassy riverbank where a man approaches a small boat. In one of the most

ambitious variations, 29 Lepic painted a large tree and snowbank

onto the plate before printing, but also sprinkled rosin on its surface,

embossing white marks that suggested falling snow. His work is notable

not only for the technical knowledge it required, but also his interest

in fundamentally reinventing etching by creating his own version of it.

29 Lepic painted a large tree and snowbank

onto the plate before printing, but also sprinkled rosin on its surface,

embossing white marks that suggested falling snow. His work is notable

not only for the technical knowledge it required, but also his interest

in fundamentally reinventing etching by creating his own version of it.

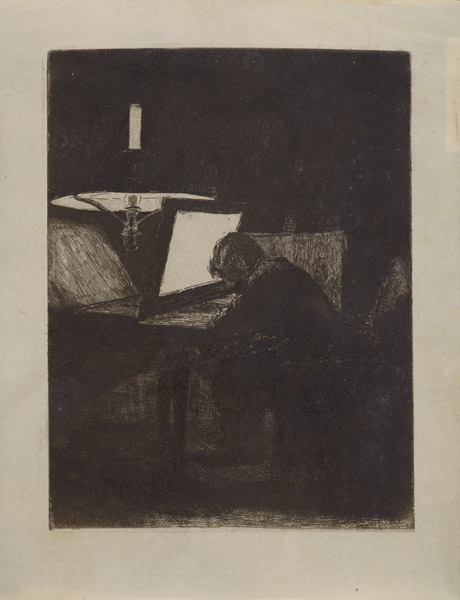

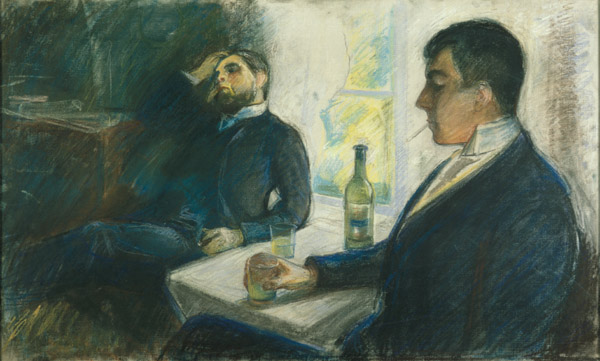

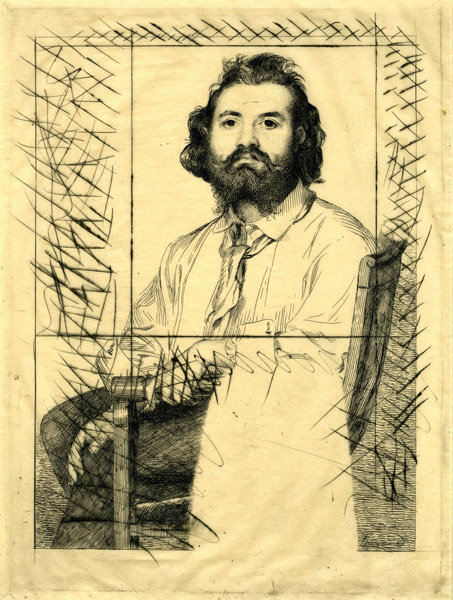

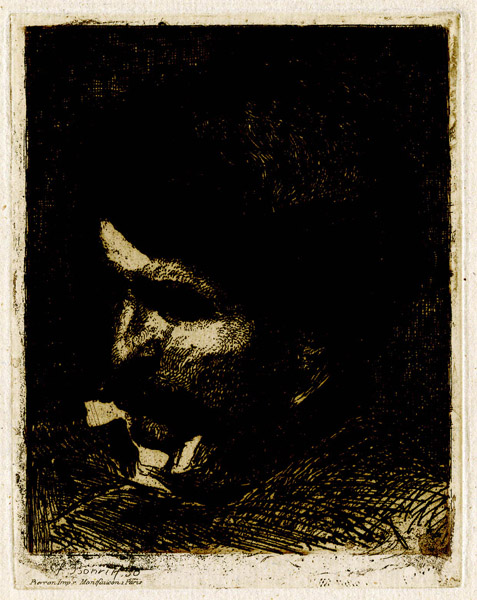

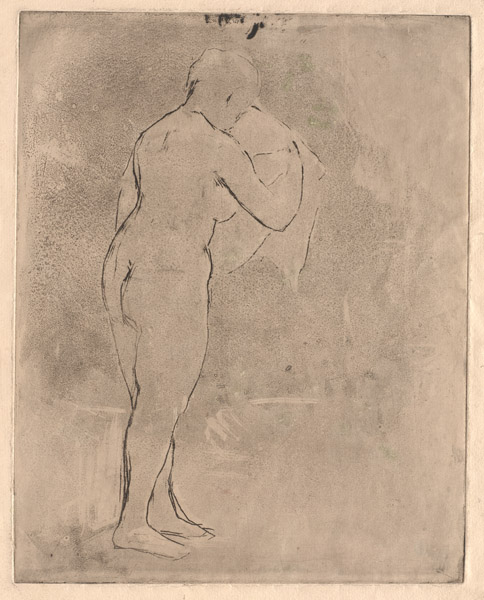

Other artists used traditional etching techniques but dramatically

altered the aesthetic of their work. Auguste Rodin was one of a number

of artists who embraced the improvisatory quality of etching and the

opportunity it afforded in sketching directly onto a prepared copper

plate. His Portrait of Henry Becque 30 was produced between

creating bronze and terra-cotta versions of a sculpture that also

depicted the controversial playwright, known for his unsentimentalized

portrayal of contemporary social mores. Rodin’s etching is situated

off-center on the sheet, giving the composition a casual tone that is

enhanced by lines loosely drawn in drypoint around the subject. Becque

is seen from three angles—frontally and from the left and

right—suggesting the print may have been a means of rethinking the

sculpture’s composition. This sense is enhanced by the depth of the

lines Rodin drew, which are far darker on the back of the left figure’s

head and much more lightly drawn in the front of the middle head,

evoking the way light might have naturally fallen. The work allowed

Rodin to use the sketchiness and freedom of drypoint to create a print

that served multiple purposes for him and his viewers.

30 was produced between

creating bronze and terra-cotta versions of a sculpture that also

depicted the controversial playwright, known for his unsentimentalized

portrayal of contemporary social mores. Rodin’s etching is situated

off-center on the sheet, giving the composition a casual tone that is

enhanced by lines loosely drawn in drypoint around the subject. Becque

is seen from three angles—frontally and from the left and

right—suggesting the print may have been a means of rethinking the

sculpture’s composition. This sense is enhanced by the depth of the

lines Rodin drew, which are far darker on the back of the left figure’s

head and much more lightly drawn in the front of the middle head,

evoking the way light might have naturally fallen. The work allowed

Rodin to use the sketchiness and freedom of drypoint to create a print

that served multiple purposes for him and his viewers.

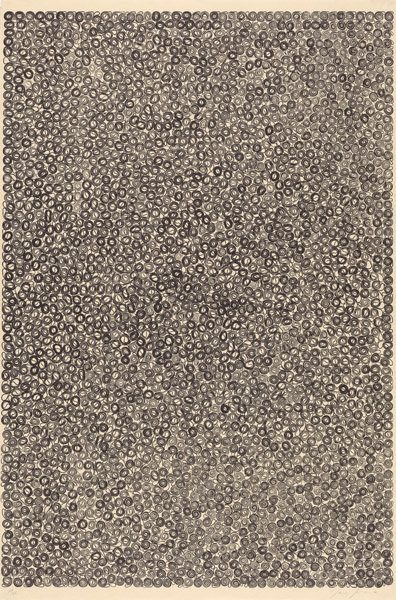

Finally, artists experimented avidly by introducing new materials and

tools and modifying those that had long existed. Mary Cassatt and Edgar

Degas, for instance, often worked with liquid aquatint—a mixture of

grainy rosin and a condensed alcohol solution that was painted on rather

than sprinkled from a pouch, as was the traditional method—giving their

etchings a crackled and irregular tonality. Mary Cassatt used this

process in her print Telling Fortunes 31 to suggest the

distance between two figures. At left, a woman appears enveloped in a

dark tone that is enhanced by lines drawn deeply into the plate to

define her form. The aesthetic of the aquatint highlights the emotional

and physical space between the two women, who sit together in a private

room entertaining themselves with a deck of cards but without directly

engaging. The stark composition and black and white tones of the image

likewise suggest an intimate but stifling situation.

31 to suggest the

distance between two figures. At left, a woman appears enveloped in a

dark tone that is enhanced by lines drawn deeply into the plate to

define her form. The aesthetic of the aquatint highlights the emotional

and physical space between the two women, who sit together in a private

room entertaining themselves with a deck of cards but without directly

engaging. The stark composition and black and white tones of the image

likewise suggest an intimate but stifling situation.

The increased availability of knowledge about the etching process allowed artists to work more experimentally than ever before in the years during and after the etching revival. Whether by interacting with other etchers or interested collectors, or by reading and working alone in their studios, artists began to see etching as an accessible and rich source for artistic production. The works these printmakers undertook during the second half of the nineteenth century intrinsically linked process, creativity, and, in many cases, subject matter to give the medium a distinct appeal to artists and collectors alike. This shift set the stage for etching, and, more broadly, printmaking, to evolve into a practice that fostered formal investigation and experimentation.

“Fut-elle jamais plus désirable, plus digne de la publicité des musées, de la recherche des amateurs? Cette fin de siècle, tant décriée, qualifiée si volontiers de décadente, restera pour la gravure originale une époque de véritable efflorescence.” Roger Marx, Société de peintre-graveurs français, troisième exposition (Paris: Galeries Durand-Ruel, 1891), 6.

Charles Blanc, “Letter from Charles Blanc,” in Maxime Lalanne, A Treatise on Etching [1866], trans. by S. R. Koehler, 2nd ed. (Boston : Estes and Lauriat, 1880), xxv.

Jay M. Fisher, Introduction to The Technique of Etching (New York: Dover, 1981), xv.

For details on these editions, see Ad Stijnman, Engraving and Etching, 1400–2000: A History of the Development of Manual Intaglio Printmaking Processes (London: Archetype, 2012), 421.

Lalanne, A Treatise on Etching, 69–72.

Léon Rosenthal, Manet, aquafortiste et lithographe (Paris: Goupy, 1925), 21.

Philip G. Hamerton, quoted in Stijnman, Engraving and Etching, 103.

Lalanne, A Treatise on Etching, 69.

Janine Bailly-Herzberg, L’eau-forte de peintre au dix-neuvième siècle, la Société des Aquafortistes (1862–1867), vol. 1 (Paris: Leonce Laget, 1972), 22.

Marianne Grivel, “La part d’ombre d’Albert Besenard: l’oeuvre gravé,” in Christine Gouzi, et al., Albert Besnard (1849–1934): Modernités Belle Époque (Paris: Somogy, 2016), 51.

“Aujourd’hui, presque tous les graveurs se mettent à imprimer leurs etudes, à varier les effets de tirage, tous possédant des presses commodes dans leur atelier.” Philippe Burty, Preface to Deuxième Exposition de Peintres-Graveurs (Paris: Galeries Durand-Ruel, 1890), 8.

This correspondence is housed at the Institut national d’histoire de l’art, Paris. For a summary, see Cécile Camart, “Note sur les archives de la galerie Sagot-Le Garrec, libraires, éditeurs, marchands d’estampes (1876–1967),” Les Nouvelles de l’INHA 10 (June 2002): 8–9.

For example, Catalogue d’affiches illustrées anciennes et modernes, en vente aux prix marqués (Paris: Sagot, 1891); Gustave Pellet, Libraire éditeur de gravures, catalogue mensuel, 1er partie (May 1894), Michael G. Wilson Collection of Félicien Rops letters and other material, ca. 1864–ca. 1910, Los Angeles County Museum of Art, Baich Art Research Library, box 5, f.1.; and Victor Prouté, estampes et livres, catalogue trimestriel 11 (November 1892), Archives Paul Prouté, S. A., Paris.

Joseph Guibert, Le Cabinet des Estampes de la Bibliothèque nationale, histoire des collections suivie d’un guide du chercheur (Paris: Le Garrec, 1926), 189–99. Philippe Burty, “L’Hôtel des Ventes et le commerce des tableaux,” in Victor Hugo, ed. Paris-Guide, vol. 2 (Paris: Librairie Internationale, 1867), 949.

In Beraldi’s personal copy of Les Graveurs du XIXe Siècle, for example, he inlaid archival documents used for research, including explanations from artists of their own works; questions directed to other experts on the merit of certain artists; and relevant, recently published criticism on printmakers and their exhibitions. See Département des Estampes et de la photographie, Bibliothèque nationale de France, Réserve, YC-34 A 8. I am grateful to Valérie Sueur-Hermel for bringing this copy to my attention.

For example, L’Estampe published “Aux Collectionneurs,” a questionnaire for readers about collecting practices, soliciting responses that appeared in subsequent issues of the journal. See M. de l’Estampe [Charles Chincholle], “Aux Collectionneurs,” L’Estampe 15 (December 12, 1897).

For more on this topic, see Peter Parshall, “A Darker Side of Light: Prints, Privacy, and Possession,” in The Darker Side of Light: Arts of Privacy, 1850–1900 (Washington, D.C.: National Gallery of Art, 2009), 2–39.

Léopold Flameng

French, 1831–1911

Tête de facture pour Imprimerie artistique de Delâtre, ca. 1860

Etching

23.8 x 17.8 cm.

The British Museum

© The Trustees of the British Museum

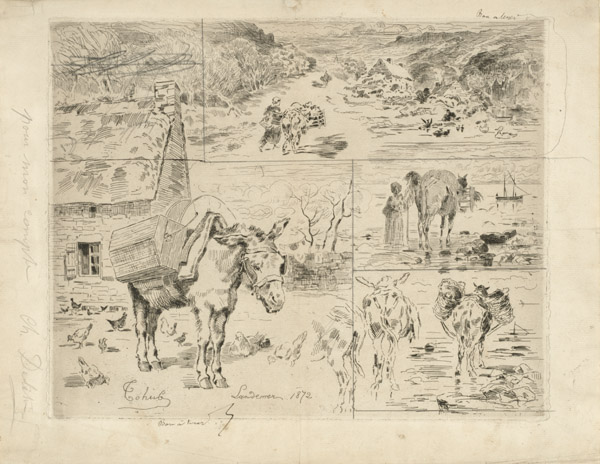

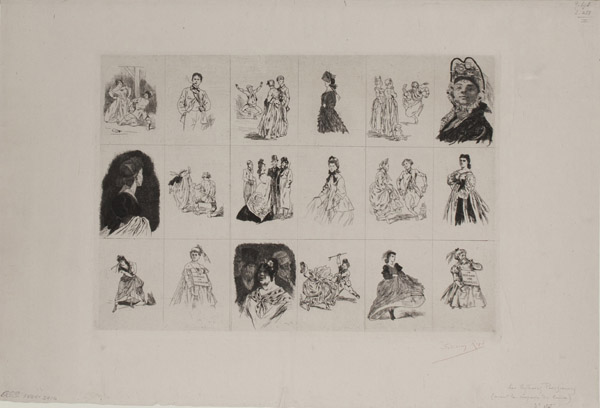

Charles François Daubigny, designer

French, 1817–1878

Auguste Delâtre, printer

French, 1822–1907

Alfred Cadart, publisher

French, 1828–1875

Frontispiece from the portfolio Voyage en Bateau, 1862

Etching on paper

Plate: 18.3 x 13.2 cm. (7 3/16 x 5 3/16 in.)

RISD Museum: Gift of the Fazzano Brothers 84.198.787.1

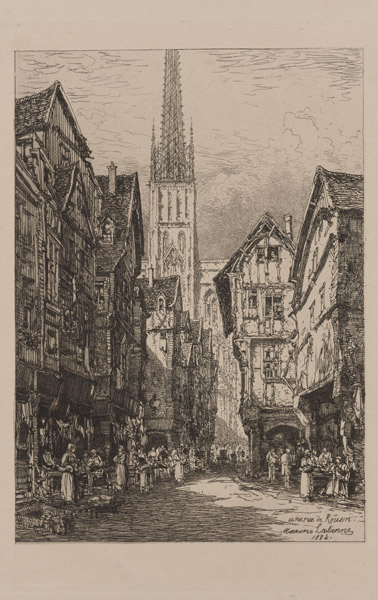

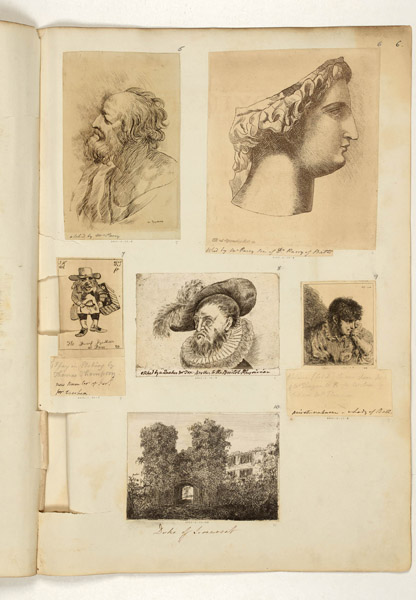

Maxime Lalanne

French, 1827–1886

A Treatise on Etching, 1880

Bound book with etchings

Courtesy of Special Collections, Fleet Library At RISD, Providence, RI

Maxime Lalanne

French, 1827–1886

A Street in Rouen (Une Rue de Rouen), 1884

Etching on paper

Plate: 27.7 x 19.8 cm. (10 7/8 x 7 13/16 in.)

RISD Museum: Gift of Mrs. Gustav Radeke 21.023

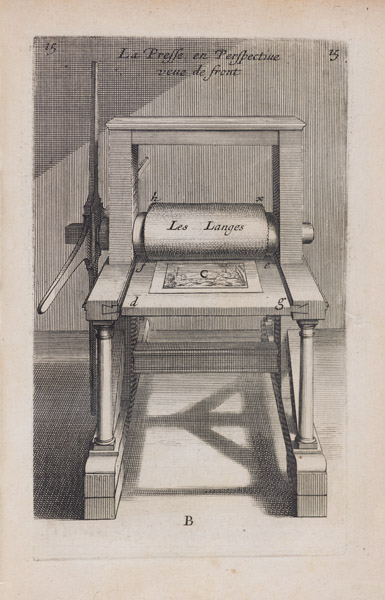

Abraham Bosse

French, 1604–ca. 1676

De la Manière de graver à l’eau-forte et au burin, et de la gravure en manière noire, 1645

Bound book with engravings

RISD Museum: Gift of Mrs. Herbert N. Straus 51.004

Etching kit (boîte complète pour la gravure à l’eau-forte) sold by Alphonse Cadart, late 19th century

Illustrated in Janine Bailly-Herzberg, L’eau-forte de peintre au dix-neuvième siècle, la Société des Aquafortistes (1862–1867), vol. 1 (Paris: Leonce Laget, 1972), 23

Illustration of portable press from A. P. Martial, Nouveau traité de la gravure à l’eau-forte pour les peintres et les dessinateurs, 1873

Georges Bottini

French, 1874–1907

The Sagot Address, 1898

Colored lithograph

Image: 11 3/8 x 7 5/16 in. (28.9 x 18.6 cm.)

Rosenwald Collection 1953.6.8

Courtesy, National Gallery of Art, Washington

Albert Besnard

French, 1849–1934

Morphine Addicts (Morphinomanes), 1887

Etching and drypoint on cream-colored, smooth wove paper

Image/plate: 24 x 37.3 cm. (9 7/16 x 14 11/16 in.)

RISD Museum: Mary B. Jackson Fund 81.206

Félicien Rops

Belgian, 1833–1898

Farewell at the Parc d’Auteuil (Les Adieux d’Auteuil), 1869

Etching, drypoint, and aquatint on white-colored, slightly textured laid paper

Image/plate: 28.8 x 17.8 cm. (11 5/16 x 7 in.)

RISD Museum: Georgianna Sayles Aldrich Fund 78.137

Félicien Rops

Belgian, 1833–1898

Farewell at the Parc d’Auteuil (Les Adieux d’Auteuil), 1869

Etching, drypoint, and aquatint on cream-colored, slightly textured laid paper

Image/plate: 28.8 x 17.8 cm. (11 5/16 x 7 in.)

RISD Museum: Mary B. Jackson Fund 75.049

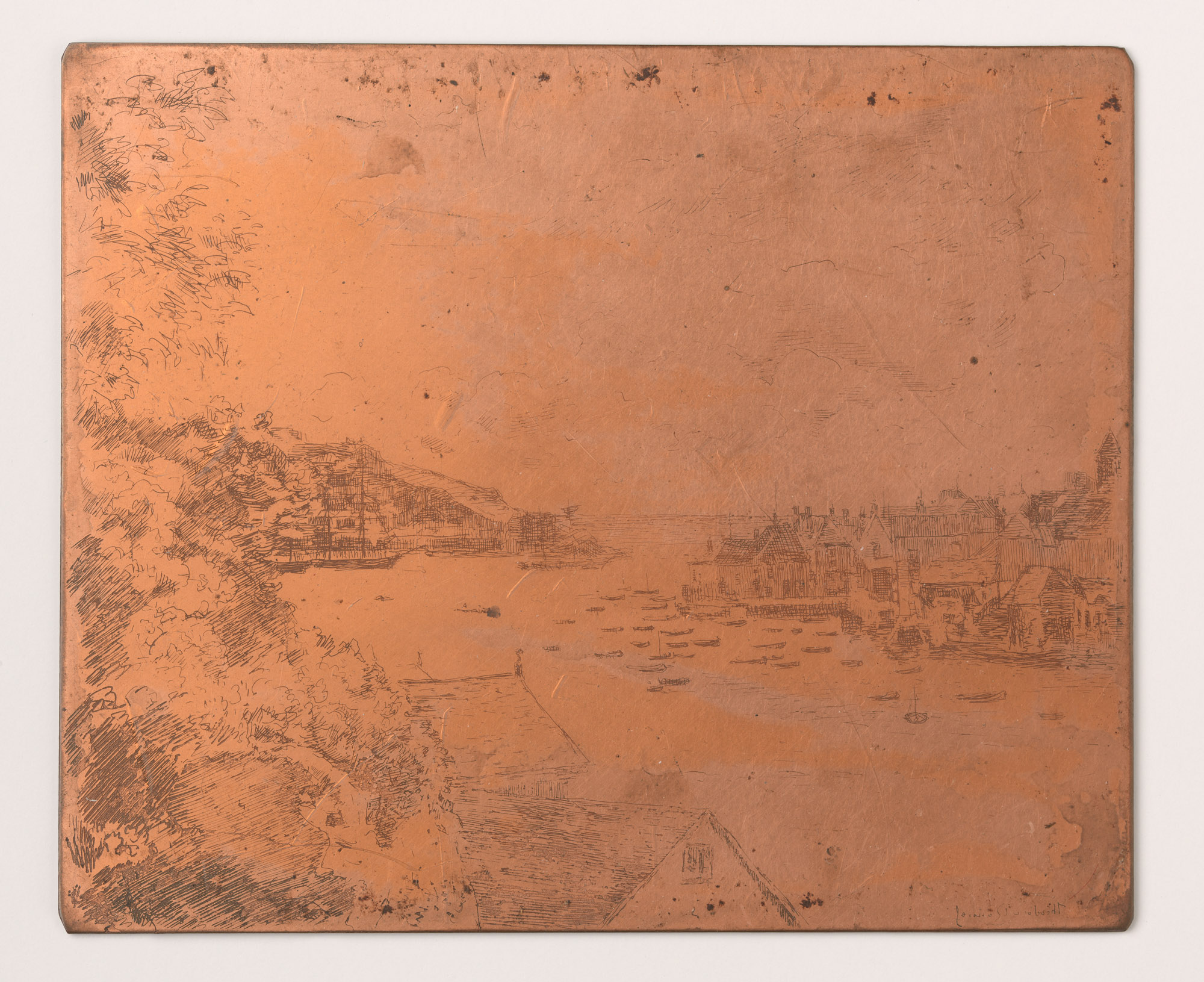

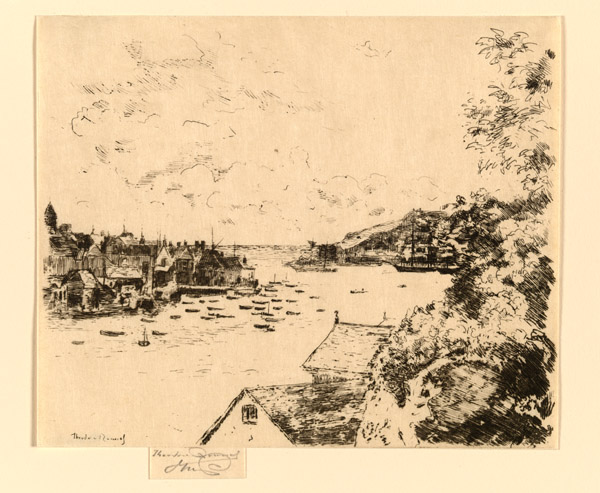

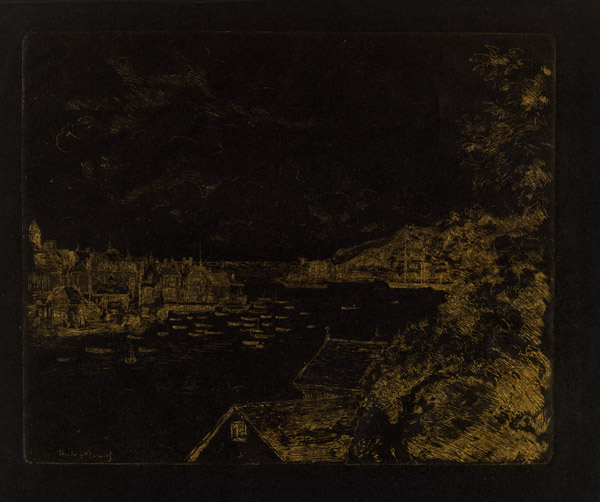

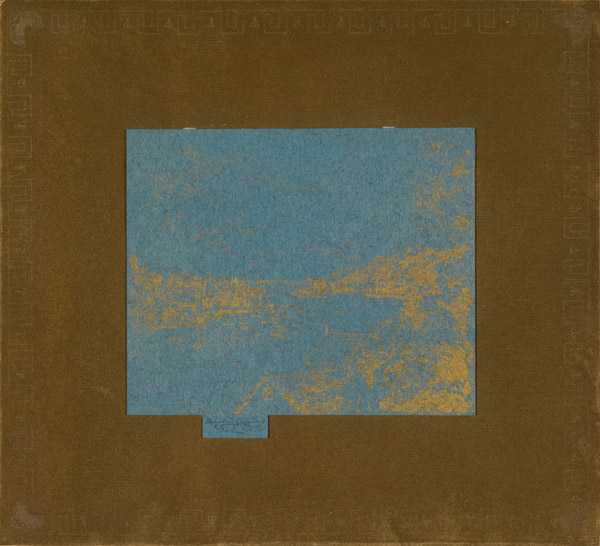

Fig. 12

Ludovic Napoléon Lépic (French, 1839–1889)

Trunk of a Chestnut Tree, ca. 1870–1876

From the series Views from the Banks of the Scheldt

Etching with monoprint inking

Sheet: 45.5 x 81.5 cm. (17 15/16 x 32 1/16 in.)

Plate: 34.5 x 74.5 cm. (13 9/16 x 29 5/16 in.)

The Baltimore Museum of Art: Garrett Collection, BMA 1984.81.21

Auguste Rodin

French, 1840–1917

Portrait of Henry Becque, 1883–1887

Drypoint on beige-colored, slightly textured wove paper

Image/plate: 15.7 x 20.3 cm. (6 3/16 x 8 in.)

RISD Museum: Gift of the Fazzano Brothers 84.198.1311

Mary Cassatt

American, 1844–1926

Telling Fortunes, ca. 1881

Soft-ground etching and aquatint on beige-colored, smooth wove paper of medium thickness

Image/plate: 13.3 x 21.3 cm. (5 1/4 x 8 3/8 in.)

RISD Museum: Esther Mauran Acquisitions Fund and Helen M. Danforth Acquisition Fund 2017.13.1

2

2 3

3 4

4 5

5 6

6 7

7

7

7 10

10 11

11 16

16 19

19 22

22

6

6 7

7 8

8 11

11 22

22 24

24 25

25 26

26 27

27 43

43

1

1 9

9 10

10 11

11 13

13 14

14 15

15 16

16

3

3 4

4 7

7 9

9 10

10 11

11 12

12 13

13 14

14 15

15 16

16 17

17 22

22 26

26

6

6 10

10 13

13 14

14 16

16 18

18

10

10 11

11 13

13 14

14 17

17 19

19 21

21 27

27 30

30 31

31 32

32 33

33 34

34

5

5 18

18